Obama Ignored Hilary’s Syria Plans for Years

Obama Stifled Hillary’s Syria Plans and Ignored Her Iraq Warnings for Years

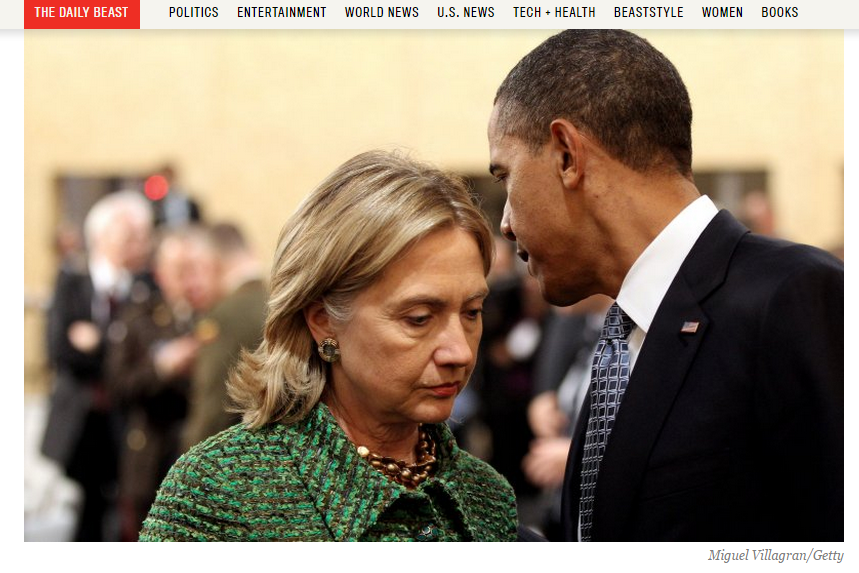

The rift between Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama over Syria that spilled into public view this week was three years in the making and was about much more than just arming the rebels.

Throughout 2011 and well into 2012, President Obama’s White House barred Hillary Clinton’s State Department from even talking directly to the moderate Syrian rebels. This was only one of several ways the Obama team kept the Clinton team from doing more in Syria, back before the revolution was hijacked by ISIS and spread into Iraq.

The policy feud has flared up again in recent weeks, with Clinton decrying Obama’s Syria policy, Obama’s inner circle hitting back, and the president himself calling criticism of his Syria moves “horseshit.” Obama and his former secretary of state promised to patch things up at a social gathering on Wednesday. But the rift is deep, and years in the making.

Clinton and her senior staff warned the White House multiple times before she left office that the Syrian civil war was getting worse, that working with the civilian opposition was not enough, and that the extremists were gaining ground. The United States needed to engage directly with the Free Syrian Army, they argued; the loose conglomeration of armed rebel groups was more moderate than the Islamic forces—and begging for help from the United States. According to several administration officials who were there, her State Department also warned the White House that Iraq could fall victim to the growing instability in Syria. It was all part of a State Department plea to the president to pursue a different policy.

“The State Department warned as early as 2012 that extremists in eastern Syria would link up with extremists in Iraq. We warned in 2012 that Iraq and Syria would become one conflict,” said former U.S. ambassador to Syria Robert Ford. “We highlighted the competition between rebel groups on the ground, and we warned if we didn’t help the moderates, the extremists would gain.”

But the warnings, which also came from other senior officials—including then-CIA chief David Petraeus and Defense Secretary Leon Panetta—fell on deaf ears. Obama’s small circle of White House foreign policy advisers resisted efforts to make connections with rebel fighters on the ground until 2013, when the administration began to train and equip a few select vetted brigades. For many who worked on Syria policy inside the administration, it was too little, too late.

In the spring of 2012, the State Department prepared several classified reports for the White House that provided evidence that the Assad regime was much more durable than thought and was not on the verge of collapse, as both the White House and State Department had assessed up to that point. Back then, the al Qaeda offshoot Jabhat al-Nusra was the main extremist threat, but Clinton’s State Department was prevented from having any relationship with the more moderate rebels who were fighting both the terrorists and the regime, often having to work through intermediaries.

For Clinton personally, the engagement of the armed groups was crucial and the White House’s forced policy of pretending that the best way to support the revolution was through the civilian opposition based in Turkey was foolish.

“Clinton understood that the guys with the guns mattered, not the people in Istanbul, that it would have regional implications, and that it could become one large operating area for al Qaeda,” said Ford. “In 2012 and the start of 2013 the most we could do was to provide help to the civilian opposition. We had no permission from the White House to help the FSA, so we did not do so.”

Toward the end of 2012, the White House allowed Ford and other State Department officials to have direct contact with the FSA but still barred even the provision of non-lethal aid. John Kerry, who also pushed to arm the rebels, finally got the White House to agree to non-lethal assistance in February 2013. The CIA ticked up its support for some armed rebel groups later that summer.

Throughout Clinton’s tenure, the White House ban on doing more to help the Syrian rebels wasn’t explicit, but over time everybody got the message. Even U.S. allies in the region, who wanted the United States to take control of the arming of the rebels, were complaining loudly to U.S. officials that the extremists were taking advantage of U.S. inaction.

“There was never a stated policy, but there was a well understood view that we were not going to do any more in Syria than we absolutely had to,” said James Smith, who served as U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia from 2009 to 2013. “The Saudis wanted us to be more involved. They were very concerned about the U.S. being perceived as weak and ineffectual.”

White House and National Security Council press staff did not respond to requests for comment.

Another State Department official who worked on Syria during Clinton’s tenure said the fights between White House and State Department staff over whether to help the rebels got heated at times. The State Department tried to alleviate Obama’s concerns about helping the rebels—it’s too risky, the arms could get lost, it won’t help—by working hard to figure out who the rebels were and how the United States could help them safely.

“[The State Department] tried to get the opposition to a place where if the president did decide to arm the rebels, it would be easier to do,” the official said. “But the institution of the State Department and the institution of the White House were not on the same page. The president didn’t budge, and Hillary had no control over that.”

Several former officials expressed exasperation this week after President Obama told The New York Times that the idea that arming the rebels would have made a difference had “always been a fantasy” and that “former doctors, farmers, pharmacists and so forth” could win the war “was never in the cards.”

They say Obama’s recent comments reveal that he was pursuing a policy that he didn’t believe in, by eventually agreeing to let the CIA arm some rebels, but only a little. This year, the president is asking Congress for $500 million to train and equip the very rebels Obama thinks are hopeless.

“It wasn’t a fantasy when the U.S. government started training and arming these doctors, farmers, and pharmacists, and led them to believe the U.S. was coming to help them,” said another former administration official who worked on the Middle East. “To them, the president’s remark is a kick in the gut.”

Clinton had to call Obama and apologize after the publication of her Atlantic interview, in which she said Obama’s “failure to help build up a credible fighting force of the people who were the originators of the protests against Bashar al-Assad—there were Islamists, there were secularists, there was everything in the middle—the failure to do that left a big vacuum, which the jihadists have now filled.”

Obama’s and Clinton’s press staffs have both tried to deescalate the feud this week and emphasize their areas of agreement. Obama is particularly sensitive about the criticism that his refusal to arm the rebels contributed to the current crisis in Syria and Iraq. In a meeting with lawmakers even before Clinton’s interview, he called that criticism “horseshit.”

But even as the White House and Clinton team tried to paper over dispute this week, White House and State Department spokespeople were still sending different messages about the Syrian moderate opposition and whether the U.S. will help them. The State Department emphasized American assistance for the rebels; the White House downplayed the efficacy of that assistance.

“The U.S. has increased the scope and scale of our assistance to the moderate Syrian opposition, including announcements made last year and a request the president made of Congress this year to fund and authorize a train-and-equip program for the moderate Syrian opposition. That’s something we think is important, and we’ve continued to increase our efforts in that area,” said State Department deputy spokeswoman Marie Harf on Tuesday, emphasizing that Assad helped start ISIS in the first place and facilitated its activities in Iraq for years. “The Syrian opposition is alive and well in Syria.”

Deputy National Security Adviser for Communications Ben Rhodes, on the other hand, emphasized Obama’s resistance to Clinton’s strategy to help the rebels, because Obama never thought it could work.

“The reason that the president was very deliberate in his decision-making there is 1) we wanted to make sure that we were providing assistance to people who we knew, so that it wouldn’t fall into the wrong hands given how many extremists were operating in that area,” he said. “And 2) we didn’t see a plan that was going to decisively tip the balance against Assad.”

By: Josh Rogin

related posts

-

A Finger Pointed at Syria for Allegedly Arming Hizbollah

by Adeena Schlussel on behalf of Daniel Lubetzky Security sources report that Syria has been delivering arms from clandestine depots in Syria to bases in Lebanon. This accusation heightens fears that Syria’s President Bashar Assad is becoming close with Hizbollah, and by extension, its friend, Iran. As part of this concern, some worry that should [...]

-

Did you listen to Barack Obama’s South Carolina Victory Speech?

Barack Obama’s South Carolina Victory speech is one of the most inspirational and powerful – and sincere – I have heard in a long time. It is also the right message that our nation and our world desperately need. After months of researching all candidates, and after seeing the way they have conducted their campaigns, [...]

-

Dennis Ross and Mideast Policy

The New York Times reports about (OneVoice/PeaceWorks Foundation Board member) Dennis Ross’s move from the State Department to the White House. It offers a lot of theories for the move, many of them probably on target. But it fails to mention one of the most important likely factors: the interplay between all these Mideast conflicts, [...]

-

Syria’s Mufti Affirms Shared Humanity of Jews, Christians and Muslims

In a remarkable sermon, Syria’s highest Sunni religious authority spoke courageously and powerfully about religions requiring humanity and respect, including these statements: “If the Prophet Mohammed had asked me to deem Christians or Jews heretics, I would have deemed Mohammed himself a heretic." Sheikh Ahmed Hassoun also “said Islam was a religion of peace, adding: [...]

-

Two Achilles Heels for Obama

Overall Obama is an extraordinarily inspiring figure, and his message is the right message for our times. McCain’s principled leadership is also inspiring, and it is clear he puts the nation ahead of himself. But Obama seems to be more in tune with what this nation and world need. That said, Obama will need to [...]

Comments are closed.