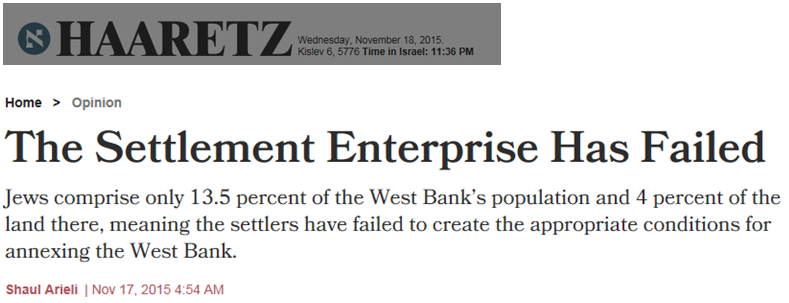

The Settlement Enterprise Has Failed

For years, the Israeli public has engaged in a seemingly important debate on the future of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. However, the absurd thing is that the argument has focused on the wrong issue: the superficial question of whether or not there is “a partner,” something that will never offer a clear-cut answer. The question also does nothing to advance the discussion even half a step beyond the two sides’ opening positions.

The unspoken part of that question is actually the key part – a partner for what? For which plan exactly? Under which conditions? In order to answer these fundamental questions, we must return to facts and figures.

While Jewish settlement in the West Bank has scattered over the years and used illegal outposts and small settlements to stick wedges into Palestinian residential blocs, the numbers paint a completely different picture. Overall, Jewish settlement in the West Bank doesn’t create a dominating presence there – not in terms of population in comparison to the Palestinian population (Jews comprise only 13.5 percent of the West Bank’s population), nor in terms of the amount of land held by Jewish settlements (4 percent of the West Bank).

In addition, the Jewish settlements do not rely on local agriculture, industry or research and development. In practice, only about 400 Jewish households in the West Bank cultivate agricultural land (with Palestinian labor). The total amount of Jewish-owned farmland in the West Bank is 100,000 dunams (about 25,000 acres), 1.5 percent of the West Bank – and 85 percent of that is located in the Jordan Valley.

There are only two significant industrial zones in the West Bank, Mishor Adumim and Barkan, and 95 percent of the workers there are Palestinian. Sixty percent of the Jewish workforce in the West Bank makes the daily commute into Israel. Based on that, the settlement enterprise – run by one section of the population, religious Zionist-messianic Jews – has failed: it has not actually created the appropriate conditions for annexing the West Bank.

Even if Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas had acceded to then-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert’s proposal that Israel take 6.5 percent of the West Bank in a land swap – despite the damage this would do to territorial contiguity and the fabric of life in dozens of Palestinian villages – Israel is not capable of offering a similarly sized area to the Palestinians. Thorough research into proposals, both official and unofficial, shows that Israel cannot possibly give up more than 4 percent of its territory – any more than that would do severe damage to the national infrastructure and dozens of Jewish communities within the Green Line.

A territorial swap of 4 percent would leave four out of five Israelis (80 percent) under Israeli sovereignty. It would necessitate evacuating some 30,000 households. Can Israel absorb such a number? The answer is yes. Israel has already successfully absorbed over a million immigrants from the former Soviet Union.

Seeing as how 60 percent of Israelis in the West Bank work within the Green Line, only 4,000 new jobs would need to be created every year for five years. Over the last decade, Israel created some 80,000 jobs annually. There will also be the need for 30,000 new housing units over five years. As of now, Israel’s potential for additional housing, based on annual demand, is many times that amount. Even the budget necessary for evacuation and reparations, assuming Israel will not receive international aid, would only require a two percent increase in the government’s overall budget.

In Jerusalem, there will be no choice but to create two capitals. But even here there are numerous ways to make it happen. Most proposals for partitioning East Jerusalem (the territory annexed by Israel in 1967 following the Six-Day War) are based on the demographic and ethnic divisions already existing in the city: 12 Jewish neighborhoods for Israel; 28 Arab villages and neighborhoods for Palestine. There are two alternatives for a solution for Jerusalem’s Old City: either sovereignty will be divided according to the demographic reality, which would leave Israel with the Western Wall, the Jewish Quarter, the Armenian Quarter and all of Mount Zion; or the entire area will be managed by an international body, with the cooperation of both sides.

With regard to refugees, the issue is much less complex than it seems – all that’s required is to agree a number. Historically, Israeli proposals put the number of refugees at about 5,000, while the Palestinians cited 100,000. Either way, the number is negligible in terms of influence on Israeli population demographics. Also, under any overall agreement, more than 300,000 East Jerusalem residents will no longer be considered Israeli residents.

However, political feasibility is required in order to make any agreement a reality. Considering the various political parties’ platforms, and the positions held by the prime minister and other cabinet members, one clear conclusion can be drawn: Israel rejects, out of hand, the establishment of a Palestinian state. During the last election, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu promised that a Palestinian state will not be founded on his watch. And his ministers in Jerusalem agree.

The Knesset is seemingly more balanced: against the 44 MKs that reject division (Likud, Habayit Hayehudi and Yisrael Beiteinu), and 23 “swing votes” (Kulanu, Shas and United Torah Judaism), there are 53 supporters (Zionist Union, Meretz, Yesh Atid and the Joint List). But the supporters generally list conditions for division, like a united Jerusalem under Israeli sovereignty or the right of return, which make reaching a consensus more difficult. Thus, on the Israeli side, support for two states for two peoples depends on four cumulative conditions: a change in the prime minister’s position; a Likud split; a change in the government’s composition; and the opposition’s criteria for partition being met. The chances for this are extremely low.

The picture is different on the Palestinian side, but no less complex. Abbas is struggling to maintain his position within the Palestine Liberation Organization and his own political path, with opposition from numerous figures – including Mohammed Dahlan, Salam Fayyad, Yasser Abed Rabbo, Ahmed Qurei (Abu Ala), Nabil Amr, Marwan Barghouti and Jibril Rajoub. Outside of Abbas’ camp, there is, of course, Hamas, which rules in Gaza: although it sometimes makes pragmatic declarations, it still refuses to recognize Israel at all, let alone make any long-term agreement.

Abbas’ ability to forge any kind of agreement that might garner Palestinian public support hinges on international and pan-Arab legitimacy, in accordance with parameters set by the Arab League, the Bill Clinton outline, or the negotiations that took place in Annapolis in 2007. These are parameters that Netanyahu refuses to accept, especially in relation to what they would mean for Israel’s borders and the status of Jerusalem.

And what does the public think? On the Palestinian side, where there haven’t been democratic elections for many years, the people are split between Hamas’ terror and opposition, and Abbas’ diplomacy. The Palestinian public feels diplomacy hasn’t achieved results or made their lives easier, and thus they’re turning to violence. According to a new poll conducted last September among the Palestinian public, 51 percent oppose a two-state solution and 48 percent support it.

Among the Israeli public, too, we must admit that the Zionist movement was never particularly excited about dividing the land. Agreements to partition in 1937 and 1947 were the result of an accurate reading of the demographic reality at the time – a Jewish minority, which prevented the establishment of a Jewish state in all the territory.

For many, the Six-Day War in June 1967 was an opportunity to strive for a Greater Israel. But a window of opportunity for an agreement with the Palestinians opened in the early 1990s, due to geopolitical changes such as the collapse of the Soviet Union, regional phenomena like the first Gulf War and events like the first intifada. These pushed the two sides to recognize one another and sign the Oslo Accords in 1993.

Today, the reality is viewed by most Israelis as more favorable. It is one that doesn’t require concessions and seemingly makes it possible to uphold the status quo – or “manage the conflict,” as the government likes to say. The economic situation, U.S. position and the weakening power of both Hamas and neighboring Arab states guarantees Israeli supremacy and stability. Changes to this perception are possible if, and only if, Israelis internalize the fact that the status quo’s ramifications could threaten Israel’s character in the future, both as a democratic and Jewish state.

Shaul Arieli is a journalist and researcher on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

related posts

-

Where Obama Failed On the Road to Mideast Peace

The Washington Post published an in-depth article on “Where Obama failed on forging peace in the Middle East”, which I strongly recommend. My analysis somewhat dovetails the article’s facts and insights: 1) When he ran for President, in contrast to Hillary Clinton’s campaign juxtaposing against Republican evil, Obama was able to transcend deep partisanship and [...]

-

Independents will play decisive role in next Palestinian elections

A new poll by Dr. Nader Said confirms that Palestinians are disenchanted with those who govern them. Even though Palestinians are traditionally very loyal to one political faction or another, they are fed up with corruption and destruction and are increasingly favor independent technocrats. Below are some of the highlights from the poll: A vast [...]

-

Likud Fined NIS 48,000 for Failed V15 Petition

The Central Elections Committee rejected the Likud’s petition against the V15 grassroots organization Sunday, and ordered the party to pay NIS 48,000 ($12,450) to the defendants. The Likud charged that the left-wing group had illegal ties to the Zionist Union and its leader, Isaac Herzog. CEC Chairman Salim Joubran ruled that the allegations were “patently [...]

-

Poll: Most Palestinians Want Peace with Israel

by Adeena Schlussel on behalf of Daniel Lubetzky A recent article in Haaretz highlights the majority opinion of Palestinians that hope for peace with Israel and wish to achieve political goals via non-violent means. Results also showed that many Palestinians have more support in Fatah leadership and less in Hamas than in years prior. Published [...]

-

Avraham Infeld Part III: Jewish Identity Is STRENGTHENED by a strong Palestinian Identity

A third particularly insightful and counterintuitive thought that Avraham shared: Arab Israelis increasingly see themselves as Palestinian citizens of Israel and that can be a very good thing for Jewish Israelis. It can help heal Israeli Jewish identity. But it needs a Palestinian culture that can flourish and not be feared, so that Palestinian citizens [...]

Comments are closed.